Oldfields

January 15, 2010

Dreaming in Clay on the Coast of Mississippi tries to capture the voices of an entire family, allowing the Andersons –-a remarkable clan of painters, potters, and poets– to tell, as often as possible in their own words, the story of the

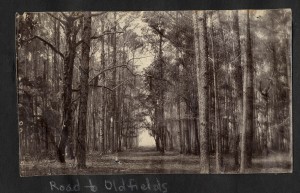

Oldfields, 1959. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College CC. "Tex" Hamill Down South Magazine Collection. Thanks to Ray L. Bellande

Pottery and of the family from the 1920s until the present.

One of my favorite parts of the book is a short story by Mary Anderson Pickard, Walter Anderson’s daughter: writer, painter, and the leading authority on her father’s work.

It’s called “Family Circle,” and Mary is describing her family’s wild and unconventional life at Oldfields, an estate overlooking the Gulf, in Gautier, Mississippi, where her father, her mother Agnes Grinstead Anderson, her grandfather William Wade Grinstead, and her siblings Leif and Billy lived during four of the painter’s happiest and most productive years, from 1941 to 1945.

The early 1940s were a time of renewal and healing for Walter Anderson: of playing with his children, watching birds and animals, observing plants and insects, and — after a long hospitalization for mental illness– making an attempt at family life. Freed from his former job as decorator at Shearwater Pottery, he had time to draw, paint and make block prints; to illustrate some of his favorite books – Don Quijote, Pope’s Iliad, Paradise Lost, Faust; to translate from Spanish part of a history of art; to grow a prodigious garden, and care for the cows, sheep and chickens. He kept Oldfield stocked with firewood, built a pottery kiln, and built a guest cottage with his own hands, in order to earn rental income. He celebrated the passing of the seasons and daily hours in a series of water-colors and lyrical “calendar drawings” that capture the life around him: his children at play, fishing, gardening, bird-watching, sailing, sketches of animals. He transformed the attic at Oldfields into a studio, bought rolls of surplus linoleum and wallpaper, and made huge prints, most of them nineteen inches wide and six feet long, and some over thirty feet. He painted his largest watercolors.

Mary Anderson adds, in a book about her father: “Missing his work in clay at Shearwater he began sculpting figurines: cows, horses, chickens, ducks, and a series of people. A farmer standing with his corn, the man who fed the animals with his bucket, a fisherman carrying a fish, a net thrower with his net, a schooner captain clutching the wheel of his ship, and two sun bathers, a man and a woman, all gracefully represent a time of life on the Gulf Coast. He made molds for his figures and cast and trimmed and painted them.”

“The name ‘Oldfields’,” Mary writes, “suggests a place left behind by change and progress. From 1940 until 1947 it was a timeless world apart despite the war and the changes going on all around it. To the artist who preferred nature to art it was a rich sanctuary where he could heal and grow. It was a world which would prompt two culminating series of linocuts in which art and nature, form and fantasy, matter and spirit would be interwoven and become one.”

Oldfields is a sacred spot in the history of American art. Such fierce intensity of creation, such loving knowledge of the natural world make it a memorable “experiment in living,” hallowed ground, like Jackson Pollock’s Studio Barn on Long Island, or Faulkner’s Rowan Oaks, or the Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio in Abiqui, or, for that matter, Walter Anderson’s own Cottage in Ocean Springs, which has recently been restored. But the historical importance of Oldfields transcends even Walter Anderson. If I’m not mistaken, it is the only remaining antebellum home on the Coast. What has become of it?

Hear Mary and Billy Anderson on their father’s life, on Mississippi Public Broadcasting.